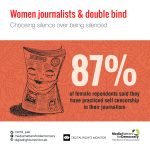

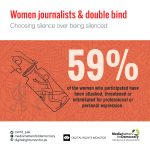

Produced by Media Matters for Democracy, this research publication maps the trend of self-censorship among women journalists in Paksitan and pratices associated with it. Based on a survey carried out with 54 women journalists across country, the report address key gaps within the censorship through a gendered lens.

Read the research here

Researcher

Annam Lodhi

Editing & Review

Sadaf Khan

Design

Aniqa Haider

FOREWARD

Women, no matter in which region, field or context they are in, are no stranger to self-censorship. The social constructs of ‘good women’ globally encourage submissive, compromising behaviour from women and self-censorship, especially in matters of importance is generally encouraged. Pakistani women are no different. Censoring ourselves, especially if our opinions are dissenting from the mainstream, is second nature. At our homes and within our families, censoring our feelings, to protect family harmony is drilled as a key ‘value’. Women who don’t complain, women who don’t assert, women who are not vocally in opposition of louder, more powerful (often male) voices.

Thus, when Media Matters for Democracy team undertook a research on self-censorship trends among journalists, the response of women journalists was of particular interest. For us, the experience of women journalists represents a double bind – as members of a community that is socially conditioned to see value in self-censorship, who are now practising a profession within which the external pressures to be quiet about matters of perceived sensitivity, women are in a doubly vulnerable position.

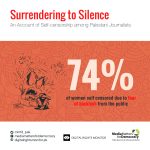

This publication is a gendered version of our earlier publication Surrendering to Silence. It focuses on the experience of the women respondents of a survey, designed to map the presence of and elements related to self-censorship in professional and personal expression by journalists in Pakistan.

The findings are sobering.

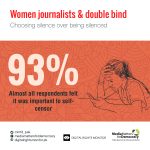

Sensitive nature of information and organizational policies are quoted as the biggest factor for self-censorship in professional settings while cultural and religious sensitivities remain the biggest silencing factor in personal expression. None of this is surprising. All of this is a cause for concern. In a country where the discussion around freedom of expression generally and the debate on threats to journalists specifically, focuses predominantly on men, the findings detailed in this research are a grim reminder that threats to media and press are not limited to a specific gender.

Additionally, given the fact that women journalists are still far and few within the news media industry in Pakistan, this choice of self-censorship within the women journalist community constitutes a doubly chilling effect on journalistic expression of women.

This research documents the experience of a precious few women in the journalistic field. It is but a mere glance at a picture that is sure to be much more complex than what our findings allow us to comprehend. Thus, this research, a gendered reading of a larger research exploring self-censorship among journalists, does not claim to be conclusive. We aim to continue to explore this issue in a more comprehensive manner. But till then, here is how 54 women journalists in Pakistan are experiencing self-censorship.

Sadaf Khan, Co-Founder Media Matters for Democracy